Welcome to part two of this mini-series on “unjazz”!

In this series, I’m using this term to describe a fascinating phenomenon in modern hip-hop and R&B. A set of rappers, singers, and producers have been making music that’s harmonically ambiguous, as jazz can be. It tolerates melodic dissonance, as jazz often does. It treats higher scale degrees as consonances, like jazz. And yet this music doesn’t sound like jazz. The extended melodic intervals no longer need to be reinforced by jazz harmonies in the accompaniment. It doesn’t “swing”. Instead, artists’ musical ears are informed by jazz influences filtered through the musical language of R&B. And these influences allow the artists to carve out new melodic and harmonic territory.

Review

In part one, we talked about how dissonances were treated in music from the European classical tradition until the 20th century. We then listed some of the new ways in which they’ve been treated in pop music since the 1950s. We then uncovered some brand-new unjazz techniques, and we assigned each an italicized catchphrase and a helpful emoji, like this:

Techniques to normalize greater melodic dissonance:

- ♻️ consonant once, consonant again: taking a tune that’s consonant over one chord and reusing it over chords where it’s dissonant

- ⚖️ stick with your scale: using the same scale over all chords, whether it would traditionally fit or not

- 🖕🏾 singing the “wrong” scale: choosing a scale that doesn’t quite match the chords, unless you’re thinking about traditional dissonances as consonances

- 😎 normalizing dissonant pitches as consonant: training us to hear a traditionally dissonant pitch like the 6th as a consonance

- 📈 elevated scale degrees: prolonging the 7th, 9th, or 11th until we hear it as a consonance

- ☰ ladder of thirds: climbing up or down a ladder of thirds to normalize the 7th, 9th, and 11th scale degrees. This ladder may well descend to the 5th and 3rd.

Techniques to permit greater harmonic ambiguity:

- 🤷🏽♀️ harmonic ambiguity: we’re obscuring the chord progression or never defining it clearly, and we’re fine with that

- 🌳 root in the voice: the voice contains the chord root, or, better still, as it’s louder and deeper than other sounds, it changes the root from what the instruments implied

We found unjazz techniques already in use as far back as TLC’s 1999 song “No Scrubs” - in R&B influenced by hip-hop. Then, in 2008, Kid Cudi’s song “Day N Nite” kicked off the modern phenomenon in which rappers sing in a manner that’s influenced by R&B, but which, like rap, is based on small musical ideas that repeat and develop. Drake took this idea and developed it into a new, original style, and we explored an acceleration in unjazz harmonic and melodic adventures in his 2013 album “Nothing Was the Same”.

Now, in part two of our series, we’ll look at Rihanna and Drake’s song “Work”. We’ll delve even deeper into Drake. Then we’ll return to R&B with the melodic adventures of SZA before ending with the present - with Doja Cat and, ultimately, the latest from Lil Nas X.

But let’s start with a review of why I think this is so original and important. After all, if you’re read part one, you may be wondering: Drake does emphasize some surprising dissonances, and some of the instrumentals he uses are quite 🤷🏽♀️ harmonically ambiguous. But is that anything new?

In fact, what Drake is doing is unlike any previous examples of spoken/sung combinations I’m aware of. In particular, rock has a long history of sing-songy, semi-spoken, semi-sung verses. But, compared to R&B, rock tends toward the harmonically stable. And these semi-spoken rock melodies are traditionally consonant. Let’s take a quick historical tour, starting in 1975.

Rap-singing in rock

Aersomith, “Walk This Way” (1975). Personally, I first heard this in Run-DMC’s joyous rendition (and you must check out this amazing oral history of how this unlikely colaboration came to be). But here we’re looking at the Aerosmith original. In the song’s verses, Steven Tyler does a sort of proto-rap, intoning rapid lyrics over a bluesy C7 chord. His vocal lines consistently emphasize a consonant tone like a bluesy third or the fifth. No melodic dissonance here.

In the chorus, Steve and friends sing a repeated two-note harmony whose top note is a highly consonant first scale degree or fifth.

| C | C |

| Eb | Eb |

| C7 | F7 |

The standard is set. We’ll consistently see in these rapping rockers that the coolness and the appeal derive from attitude, sonic distortion, and harmonic stability - not from melodic dissonance or harmonic ambiguity.

Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers,

“Mary Jane’s Last Dance” (1994). The verse is built on an Am - G - D - Am progression. Petty’s melody is half sung, half spoken, with one clear pitch - the bluesy third, C. It’s another highly harmonically stable rock song.

The chorus shifts to A major through a beautiful and surprising route, pairing an E minor chord with a melodic jump to a harmony whose top pitch is F#. The F# is quite remote from the C prolonged by the verse, and it forms a dissonant 9th over the E root. But then the this melody gracefully descends F# - E - D - C# before landing back up on E, a stable 5th scale degree over an A major chord:

| F# E D | F# E D C# | E |

| Em | Em | A |

This moment of dissonance is quite beautiful, but it settles quickly and gracefully into a stable consonance.

Red Hot Chili Peppers,

“Dani California” (2006). In the verse, Anthony Kiedis sing-raps a repeated pattern that descends from B to A, over the same Am - G - Dm - Am progression that Mary Jane was dancing to:

| B A | B A | B A | B A |

| Am | G | Dm | Am |

Having done this twice, he next sings a little tune that simply follows the chord roots:

| A | G | D E | D A |

| Am | G | Dm | Am |

This example usefully shows what we’d expect from a frontperson who began their career as a rapper before branching out into singing. Put simply, Kiedis sings notes that are easy to find. He doesn’t need to worry about constructing innovative melodies or seeking out dissonances! This is why Drake is so noteworthy.

(now for a brief “pop” quiz… what producer was involved with all three of these songs? (Hint: his name rhymes with “Bick Bubin”.))

The Neighborhood, “Sweater Weather” (2012). Finally, let’s take this into the present. As I began writing this article, “Sweater Weather” had returned to the U.S. charts. With its emphasis on creatively resolved melodic dissonances, it maintains some fascinating harmonic ambiguity, although dissonances are still resolved in a conventional fashion.

“Sweater Weather”’s second verse features some rapid-fire talk-singing. Like in “Mary Jane’s Last Dance” and “Dani California”, a melodic pattern repeatedly descends to a consonant first scale degree. Even in this more dissonant song, the rap-singing is not harmonically adventurous.

| C B♭ G | C B♭ G | C B♭ C | C B♭ G |

| E♭ | Gm | Cm B♭ |

Now, of course, this brief survey shouldn’t lead us to conclude that rock has never explored extreme melodic dissonance. Remember what I said in part one about “Black Hole Sun”? (You really need to at least watch the video.) Check out psychedelia, some prog rock, and more outside the pop charts.

But if you want to hear a modern artist who’s popular and who follows Drake more closely outside the world of hip-hop, look to country music. Check out Sam Hunt, whose rap-like verse in “Breaking Up Was Easy in the 90’s” emphasizes a lot of 7ths and AutoTune. (This incredibly bleak video bears watching too.)

I should also mention that plenty of singing rappers have ignored Drake’s unjazz adventures. Of course, that’s fine. There’s plenty of ways to make a successful song. It’s just this article focuses on dissonance and harmonic ambiguity. It’s actually much easier to find these innovations among modern female R&B singers than among singing rappers. Speaking of which - now we’re ready to look at “Work”!

Triumph of the unjazz

“Work”

If you read part one, you’ll remember that a key inspiration for this article was a debate about Rihanna and Drake’s song “Work”, from Rihannas’s 2016 album Anti. The discussion centered on the basic question: what key is this song in? Its chord progression starts on a C# minor, rooting it in that key. And yet all the song’s melodies lie firmly in a B major scale - or, if you prefer, G# minor. And the tune keeps emphasizing D# and F#, which would be typical in songs in B major or a bluesy G# minor, but which don’t fit C# minor. What’s going on?

We’ll look at the parts Rihanna sings, and then we’ll check out Drake’s contribution.

Rihanna’s bit

First, we’ll note that the song is based on a repeating four-chord progression:

| C#m | D#m | E | F# |

The song’s vocals begin with the chorus melody. This repeats a two-bar phrase which varies slightly from line to line, but generally goes much like this:

| D# B B C# | C# C# D# F# E D# | D# B B C# | C# C# D# F# E D# |

| C#m | D#m | E | F# |

Right away, the melody is highly unusual. In the past, we’d expect such a melody to be paired with chords that implied an entirely different key. Like, B major:

| D# B B C# | C# C# D# F# E D# | D# B B C# | C# C# D# F# E D# |

| B | C#m | B | C#m |

Or, more characteristic of the style, G# minor:

| D# B B C# | C# C# D# F# E D# | D# B B C# | C# C# D# F# E D# |

| G#m | E | G#m | C#m |

But… no. Rihanna sings this tune over a progression that contains nary a B or G#m chord. And the song’s much more interesting this way. It’s another example of 🖕🏾 singing the “wrong” scale - choosing a scale that doesn’t quite match the song’s chords, but will bring out unjazz dissonances. Pairing this tune with these chords has the wonderful advantage of hitting intervals that are traditionally dissonant on every downbeat. Here are the pitches that land on downbeats, over the bass notes:

| D# C# | D# C# |

| C# D# | E F# |

I’d argue that this tune prolongs this D# and C#, with the other pitches filling a more decorative role. You can hear that if I play the tune again while emphasizing those notes:

Macroscopically, the tune resolves twice from D# down to C#. The second D# - C#, occurring over the E and F#, is a traditional resolution from a dissonant major 7th to a consonant perfect 5th. But the first D# - C# occurs over C# and D# in the bass, meaning that a dissonant 9th (D# over C#) “resolves” to a still-dissonant 7th (C# over D#).

This makes more sense if we consider this music as unjazz, incorporating a harmonic sensibility drawn from jazz without needing jazz chords or rhythm. You can hear this if we add in the missing jazz chords. I’ll play these while subtly emphasizing the D# and C# the melody prolongs:

| D# B B C# | C# C# D# F# E D# | D# B B C# | C# C# D# F# E D# |

| C#m9 | D#m7 | EM7 | F# |

Rihanna is 😎 normalizing dissonant pitches as consonant. Once we’ve heard this tune a few times, it sounds completely expected, not jarring at all, even without the harmonic support the jazz chords would have provided. I think that, once again, modern vocal production helps this along, making Rihanna’s voice sound so thick that we assume it must be consonant.

In fact, we will hear these jazz chords in the actual song, but not until 1:28, in a little bonus section following the second chorus:

Notice also that, if we consider the melody to be in C# minor, it never goes below the 7th scale degree: 📈 elevated scale degrees. Rihanna’s exploring the space from that B up to F# - in other words, from the 7th to the 11th - while spending plenty of time on D#, the 9th. Like “No Scrubs”, this tune is built on the 7th, 9th, and 11th degrees, but does even more to treat those as consonances. Yes, it’s our good old ☰ ladder of thirds!

Rihanna’s verse begins by playing with the same melodic language as the chorus melody. Now that the chorus has established the language of unjazz, the verse can draw from it in ways that resolve dissonance even less. Here’s how it begins:

| F# B | C# G# | D# C# B | C# G# |

| C#m | D#m | E | F# |

Whereas the chorus arrived at the F# and left it by stepwise motion, now Rihanna simply starts right there - on a dissonant 11th. And then she feels free to drop down a fifth from there to the B, the 7th, before heading back up to the C#, which now a dissonant 7th over the D#m. Then touching almost inaudibly on the G#, another dissonant 11th. She’s telling us: these jazzy elevated scale degrees are consonances, and I can use them anytime I want to. As in the chorus, the C# is normalized over the F# chord as a consonant 5th, but she makes no attempt to resolve the F# or G#.

I won’t go into Rihanna’s entire fascinating verse in detail. It’s not structured like a traditional song verse at all. It’s more like a rap, where she simply plays with ideas over a repeated instrumental for a given space of time. Or like jazz, where an instrumentalist explores melodic ideas and motifs. To me, the way she develops her material doesn’t feel improvised, though, but highly deliberate, like the Renaissance composer Josquin des Prez, like other older European composers, or like Indian classical music. This comparison shouldn’t be surprising; it’s simply a natural way to develop musical material, one that’s occurred to various musicians across numerous cultures.

Suffice it to say that, from 0:26 to 0:42 in the track, every phrase that starts over the C#m chord begins with an F# or a D#, and every phrase that starts over the E chord begins on D#. These pitches are an 11th, 9th, and 7th respectively.

At 0:42, we hear a new keyboard riff that goes B-A#-F#, holding the F# all the way until the F# chord comes in. It’s really the first time that the dissonant F# has been resolved to a consonance. Interestingly, it’s also the only time in the song where I’ve noticed a melodic A#. Like in “No Scrubs”, this pitch in the scale is skipped.

Before leaving the verse behind, let’s look at two more interesting moments. At 0:53, Rihanna sings a new melodic idea three times, an intensification which signals the impending end of the section:

| D# C# B | G# D# C# | D# C# B | G# D# C# | D# C# B | G# D# C# |

| E | F# | C#m | D#m | E | F# |

This phrase repeatedly moves down the ladder of thirds from D# to G#. This is the first time Rihanna emphasizes the low G#. She could have taken this opportunity to introduce a new consonance, since the G# would be 5th over the C#. Instead, the G# only appears over the D#m (where it’s a 4th) and the F# (where it’s a 9th).

This phrase feels especially like a prolongation of a C#m9 chord. Coupled with the B-A#-F# riff’s sustained F#, it also feels like a C#m11 - or, if you’re thinking about the A#, a C#m13.

Then, instead of building up to the return of the chorus, the verse just kind of fizzles out. Here’s its final phrase, at 1:03:

| F# B C# | B | F# B G# | F# F#(high) D# C# B |

| C#m | D#m | E | F# |

It’s the first time we’ve spent much time on the low F#. In fact, this melodic bit spans the entire octave from low F# to high F#, once again emphasizing this curiously dissonant pitch. I’m especially interested in the first melodic phrase:

| F# B C# | |

| C#m | D#m |

It starts once again on the 4th scale degree (a.k.a the 11th), then moves to the 7th scale degree, before ending on a C# that’s mainly heard as a 7th on the D# chord. This would normally be odd, but it fits perfectly with the melodic language Rihanna’s taught us through 😎 normalizing dissonant pitches as consonant. The chorus tune spanned the range from B and F#, with an emphasis on C#. This little melodic riff summarizes that melody, and the song’s entire melodic language, in three pitches. Just to drive that point home, Rihanna returns to it at the end of the track, at 3:18, repeating F#-B-C# as the song fades.

Drake’s bit

Now let’s take a quick look at Drake’s verse, which starts at 2:09. Here’s how it starts:

| G# F# D# | C# F# E | D# C# B | B D# C# B |

| C#m | D#m | E | F# |

Drake begins by gradually descending, singing notes that fly free from the song’s rhythm, from G# down to B, covering all the melodic pitches used in the song - G#, F#, E, D#, C# and B. He lands on a B over the F# chord, a characteristic Drake 4th. Then, to make his point, he covers the same distance again, but much more quickly, twice. Drake’s announcing to us that he intends to sing in the same B major (or G# minor) scale as Rihanna: 🖕🏾 singing the “wrong” scale.

Next, at 2:21, he cuts this scale down to a quicker riff that goes D#-E-D#-C#-B. He sings this four times in a row. He’s doubling down on the B, like he was resolving to it as a consonance, except that the B always arrives over a D#mi or F# chord. In fact, all of his melodic ideas descend to this B until 2:52 in the track.

If the song was in the key of B major, these repeated resolutions to a B would be incredibly consonant, and incredibly boring. That’s why it’s such a brilliant move in a song that’s so rooted in C# minor. If you’ve read part one of this article, you’ve already seen this is something deliberate, something characteristic of Drake’s style, something that makes his small, repetitive melodies off-kilter, interesting, unpredictable - dissonant. Later in this article, in “God’s Plan”, we’ll see Drake returning again to descending dissonant six-note scale segments.

We’ve looked at Drake in part one, and we’re about to look at even more Drake, so I won’t talk more about his bit here. Just give it a listen with these words in mind!

So - what key is this song in?

For me, the song’s in C# minor, and its melodic content comes from the C# Dorian scale - the same pitches contained in B major or G# minor. The Dorian scale incorporates a flat 3rd and flat 7th, which makes it not uncommon in songs that are blues-influenced, like much of pop has been since 1956. Songs in major scales often include a flat 7th - which makes them Mixolydian - and songs in minor scales may well have a sharp 6th, like this one. Nothing in the song particularly strengthens any of the chords in its repeated progression. The song lacks cadences or moments where the melody resolves strongly - so for me, the song is in the key of the first chord, the chord it keeps returning to - C#m.

You may say that the song’s in G# minor or B major because its melody uses the corresponding scale. You might also say that the melody’s emphasis on the notes B, D#, and F# pushes it into B major. If you’ve read this article, though, you might see that this doesn’t help your case, since it’s characteristic of unjazz to emphasize scale degrees like the 7th, 9th, and 11th. It’s just a different way to think about the key of C#.

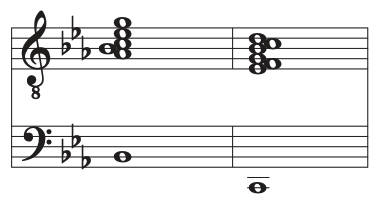

To me, it feels as if the song prolongs one long C#m11 chord - a chord that’s highly characteristic of soul music of the 1970s. It’s quite close to a B/C# chord, the flavor of the 11th chord that screams: “disco!" Listen to this chord, then listen to the song, and notice how the chord encapsulates the sound of the song.

So, for me, this song is a straightforward unjazz take on C# minor. But if you’ve read all this and you say you hear this song in B, G# minor, or E - I wouldn’t say you’re wrong. Pop songs tend to lack the strong cadences characteristic of Western classical music, and plenty of songs that are based on repeating chord progressions aren’t definitively in any particular key. If you say this song is in B major or G# minor because it uses pitches from those scales, you can derive useful analytical insights from considering the song in those ways too! In any case, 🤷🏽♀️ _harmonic ambiguity _is characteristic of unjazz too.

Other songs on Anti push the harmonic envelope in ways that are especially striking for one of the biggest pop stars of the modern era. In “Woo”, she sings a strong, Rihanna-like catchy tune over an avant-garde backdrop of distorted guitars and destroyed sounds. In “Needed Me'' she rap-sings over an instrumental whose pitches are barely definable - a combination of pop and pure experimentation. We could talk about Rihanna all day, but I really want to follow Drake into the present - and then explore the wild world of SZA.

Drake, again

In part one, we delved into the unjazz innovations in Drake’s 2013 album “Nothing Was the Same”. Now, let’s see how Drake has continued to push the harmonic envelope to the present day, both by using 🤷🏽♀️ harmonically ambiguous instrumentals and creating melodic ideas that we can only call… unjazz.

“God’s Plan” (2018)

In “God’s Plan”, Drake once again sings firmly in a scale that’s not what the track would normally imply: 🖕🏾 singing the “wrong” scale. It’s also a fine case of 🌳 root in the voice, like we saw in “Day ‘n’ Nite”.

The song is based on a distant-sounding organ which loosely defines Am9 and GM9 chords. (This organ is played a little north of A-440 tuning, so these pitches are approximate. And I can’t hear whether that C in the first chord is really there.)

This sample loosely defines a G tonality, but the chords sound as much like CM7 and Bm7 as they do like Am9 and GM9. We don’t really hear what key we’re in until Drake’s vocals enter. This happens at 0:13, as Drake’s voice descends eight times from E down to G in the G major scale:

| E D C B | B A G |

| Am9 | GM9 |

This long descent down a six-note scale is exactly what he did in “Work”. Once again, the descent lands intentionally and repeatedly on a pitch that isn’t quite what we expected. In this case, though, instead of landing on a dissonance, he lands on the pitch that defines the G major tonality. The bass hasn’t entered yet, so 🌳 Drake’s low voice serves as the bass, defining the key. Again, this is unusual. But Drake knows that Autotune and layers of effects will make his voice strong, thick, and precisely in tune. His voice is the most prominent instrument in the mix. In fact, in this song, it’s the only instrument that expresses clear pitches.

When the bass actually does come in, it’s so low that it’s tough to make out. Under A minor chords, it plays an A. Under the GM9, it sometimes hits B more strongly, sometimes a G, and sometimes it just makes really low sounds. When the bass plays a B, the chord we’ve called a GM9 sounds much more like a Bm7.

This song is not as 🤷🏽♀️ harmonically ambiguous as others we’ve looked at, but I do think the way that Drake’s voice defines the tonality is pretty cool - and highly characteristic of the style he’s created.

(Oh, and will you please watch the video?)

“Laugh Now, Cry Later” (2020)

“Laugh Now, Cry Later” features both a 🤷🏽♀️ harmonically ambiguous instrumental and a vocal that 😎 normalizes traditional dissonances as consonances. It’s a wonderful example of unjazz, a great place to leave our exploration of Drake’s music.

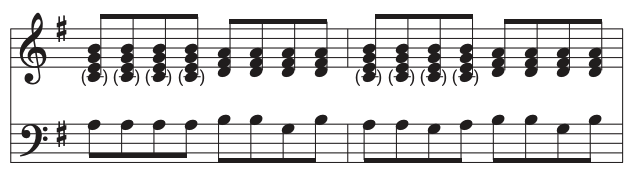

Let’s start with the instrumental sample, played by the conservatory-trained Rogét Chahayed. This riff’s surface simplicity masks a deeper complexity, a common feature of higher-quality pop music. It starts with a FM7 - Em7 - Dm7 progression:

This pattern starts to repeat, but before it finishes repeating, it cuts itself off two beats short, then sounds like it’s starting to repeat with slightly different chords, before cutting that off and actually repeating everything that’s just happened. Here’s the entire sample:

This simple trick means we’re always a bit off-kilter, not quite sure when the pattern starts and unclear on the downbeat. It makes a standard four-bar phrase in 4/4 feel like it dips into 6/4. When the drums enter, the rhythmic ambiguity only grows. Switched On Pop has covered this in excellent detail.

Note that FM7, Em7, and Dm7 are technically jazz chords, but the way they’re played and deployed feels nothing like jazz. That’s why we keep calling this “unjazz”!

Normally we’d expect FM7 - Em7 - Dm7 to function as IV-iii-ii in C major. These chords are begging to resolve to C major, like this:

But in this song, they never do. Instead, the song continually reanchors itself on the D minor seventh chord, never descending to C. Somehow, to me, it sounds impossibly deep - like the chords are continually sinking into a subbasement. Thus this sample is both rhythmically and 🤷🏽♀️ harmonically ambiguous. Is the song in F major? D minor? Something else? If I had to choose, I’d choose D minor, but if so, it’s a version of D minor I’ve never heard before.

Drake opens by singing the word “Whoa” twice. Right off the bat, he chooses some odd notes, signaling that he will continue to explore his own harmonic language in this song.

| G E G E D |

| Dm7 |

It’s reminiscent of a standard vocal riff, but it’s divorced from its customary harmonic and rhythmic contexts. The G and E, 11th and 9th scale degrees, only half-heartedly resolve to the 1st scale degree of the D.

Next, at 0:06, the main section of the song begins. I won’t call it a verse, because, like increasingly many modern pop songs, this song lacks a recognizable verse or chorus. During this section, Drake repeatedly glides down a pentatonic scale. He covers the distance of a sixth, just like the repeated descents we saw in “God’s Plan” and in “Work”.

| G | A G E | E D C | D C |

| FM7 | Em7 | Dm7 |

This material is an expansion of the small melody Drake sang on “Whoa”, extending it by a single pitch in both directions.

This tune is more consonant than much of what we’ve seen in this article. Over the F chord, Drake emphasizes the A, a consonant third. Over the Em chord, he lands on an E, a highly consonant unison. On the Dm, he lands on a D, but then continues on to rest on a C, the 7th scale degree. He then repeats this twice, 😎 normalizing the 📈 7th as a consonance. Likely the C was inspired by the strong C in the melody in the sample, which, like Drake’s melody, descends before landing on an oscillation between D and C. But the C sounds quite different where Drake sings it, two octaves lower, the lowest distinguishable pitch in the arrangement.

Drake succeeds so well in normalizing C as a consonance that the D begins to sound like a dissonance, even though it’s the root of the Dm chord. Between the first and second repetitions of the main tune, and again between the second and third repetitions, he sings the word “baby” on E-D. To my ears, the E sounds more consonant than the D.

After the third repetition, at 0:26, Drake sings “baby” on a quite odd C-G. The G makes some sense because it becomes a 7th scale degree over the incoming Ami chord (instead of another dissonant 11th over the Dmi), but it still shows that Drake is reaching for unconventional unjazz tones.

Then the drums enter, and Drake sings variations on this melody until the end of his section. At first, the descents end on a nice consonant D. But then he starts to end on C again, sometimes even E. In Drake’s world, it’s fine to end on a traditional D, and it’s equally fine to end on a pitch that’s one note away. That’s a little like R&B, a little jazzy. It’s unjazz!

At 1:28, Lil Durk’s part begins. Perhaps inspired by Drake, he emphasizes the notes C, D, and E. In fact, his part consists mostly of these notes. But he is more harmonically conventional. Each of his phrases resolves to D, the first scale degree. Of course, some of those final D’s do appear over the Emi chord, making them 7ths. The individual chords matter less than the overall harmonic language, an example of ⚖️ stick with your scale. And the harmonic ambiguity that’s introduced aren’t created by someone who can’t hear harmonies. It’s intentional, a positive attribute of the music! Melodic dissonance - and the song’s rhythmic ambiguity - add tension and create energy, making static music dynamic, making it thrilling.

Listening to Drake’s music over the years, sometimes it feels like he’s choosing the most harmonically vague beat to sing over, just to challenge himself. He’ll simply choose a scale and run with it, and because he’s chosen some pitches that are in the instrumental, and he’s got the loudest, most defined notes, it works. Check out, for example, “Own It” (2013) and “Can’t Take a Joke” (2018).

I wish we could follow Drake into 2021 by spending some time with the wonderful, swirling, harmonically unstable instrumental in this year’s “What’s Next”. But we really need to get on to SZA!

SZA

With SZA, we arrive at the thrilling conclusion of our unjazz story. We first found unjazz in late-90s R&B, the sort that was influenced by hip-hop. Then, when rappers began to sing more in the late 2000s, they were in turn influenced by those R&B singers. In “Work”, we saw how R&B singers and rappers were still learning from one another. And now we turn to a modern singer, SZA. SZA is often labeled as “R&B”. But, to my ears, what she is doing, along with a number of other artists classified this way, is building on R&B, hip-hop, and jazz traditions to create something entirely new - something unjazz!

Let’s start with one of the songs that inspired this investigation: SZA’s 2020 hit “Good Days”.

“Good Days”

This song is based on an instrumental created by Los Hendrix and Nascent. As with many of the songs we’ve discussed, it uses jazz harmonies, though it’s not what you’d call funky. It’s not even particularly “jazzy.” It’s possible to use extended sonorities that are characteristic of jazz without playing jazz. Just ask the classical composers like Brahms and Debussy.

Once again, we’re dealing with a sample that’s diffuse, suffused with reverb. Since the guitar plays individual notes, not chords, the precise chord extensions - say, whether a given chord is a 7th or a 9th - are a matter of opinion. But they’re certainly something like this:

| EM9 | C#m9 | EM9 | C#m9 AM7 | EM9 | C#m9 | EM9 E#° | A Am |

(Note the rare case of a diminished chord in a modern pop song! This specimen is a passing chord between E and what we’d expect to be an F#m, but is actually a false-cadence-like A.)

SZA’s vocal phrases don’t line up with the instrumental as it repeats, further contributing to the song’s hazy, unstructured feeling.Thus it’s hard to determine where this beat actually “begins”, the sort of rhythmic ambiguity we frequently saw in Drake’s music. The way I’ve just described the sample, SZA actually starts her vocals in the third measure. I still prefer this interpretation because it allows important events - like the first time the drums come in, and the entry of Jacob Collier’s backing vocals - to kick in during the first measure.

Instead of singing distinct verses and choruses, SZA repeats and develops melodic ideas, just as rappers repeat and develop rhythmic ideas, and as Rihanna did in “Work”. Let’s look at the first bit she sings, at 0:24 in the track. We’ll consider the two measures up to the word “iceberg” as her first melodic phrase.

| G# E F# E F# C# B F# C# B | F# C# B F# G# F# G# F# |

| EM9 | C#m9 AM7 |

SZA starts by descending from a consonant G# (the third) through a passing F# to a consonant E (the first scale degree). Four pitches in, the tune is quite conventional. But then she repeats, three times, the notes C#-B-F#. Instead of passing through the F# like it was a dissonance, she leaps up to it like it was a consonance. The first time, the F# occurs over an E chord, making it a 9th or 2nd. The second time, it’s an 11th or 4th over a C#m chord. The third time, it’s a 6th over an A.

How does SZA treat this traditional dissonance? After hitting the F# three times, she does move back up to the G# that began the phrase as a consonant third. But this G# now occurs over an AM7, where it’s a major 7th. Essentially, she’s resolving a dissonance to another dissonance. She then oscillates between G# and F#, relishing the 📈 elevated scale degrees,😎 training us to hear them as consonances.

SZA then repeats this first phrase, starting again on a G# over an E chord, finally resolving the dissonance. But the second phrase again emphasizes the dissonant F#. Although F# is at no point a consonance, it’s the focus of her melody thus far. Like Drake or Rihanna, SZA deliberately heads for and emphasizes a pitch that’s a step away from a consonance. And it’s one of our favorites in this article - a 9th.

At 0:38, SZA starts her third melodic phrase on a high B. Finally, it’s a nice consonance, the 5th scale degree over the E chord! But, after touching this note briefly, she descends to a low B. Moving from high B to low B would normally be a nice way to prolong the consonance. But the low B occurs over the E# diminished chord. Though that diminished chord does contain a B, a tritone over the root is hardy consonant. Then she quickly rises back up to an F# and a G# over the A chord, stopping on G#, breaking off the phrase with twin dissonances.

This sets the tone for the rest of the song, during which SZA explores variations on those opening phrases without regard to traditional notions of verse and chorus. Sometimes she pauses to hit a consonance, but not terribly often. More often, she reaches for 6ths, 7ths and 9ths. Often she pauses after ascending to that F#, which is always dissonant.

To experience SZA’s harmonic adventures, I encourage you to simply listen to the rest of the song. Before we leave it, though, let’s just touch on a contrasting bit SZA begins at 1:35, on the words, “Feeling like, feeling like Jericho”.

| D# C# D# B | B G# D# B G# C# B | D# E F# D# E F# D# E F# B | D# E F# B G# F# B G# |

| EM9 | C#m9 | EM9 E#° | A Am |

She starts with an unprepared leap up to the D# over the E chord, a major 7th. She sort of resolves this D# down to C# - but that’s still a dissonant 6th. By the time she gets to the consonant B, she’s basically on to the C#m chord, where the B is a 7th. To SZA’s unjazz-influenced ear, the 7th is a consonance, and she trains us to hear it the smae way.

At 1:43, she sings D#-E-F# over the E chord, rising back up the ☰ ladder of thirds from the 7th to the 9th. She then repeats this D#-E-F# twice, even while the harmony shifts to a E#° over which all three notes are utterly dissonant. She simply persists until the harmony migrates to A, at which point she sings D#-E-F# again. It’s not particularly consonant there either, but our ears accept it, thanks to the principle of ♻️ _ consonant once, consonant again_. Of course, that means you have to already accept the idea that D#-E-F# is consonant over the E chord, even though the only traditionally consonant note there, E, is treated as a passing tone between the oddly consonant D# (a 7th) and the F# (a 9th). For SZA, though, these extended jazz tones are simply 📈😎 consonances.

Back in part one, I said that when I first heard this song, the voice seemed to soar impossibly high above the bass. I now think that feeling comes from SZA’s emphasis on upper scale degrees. And her complex rhythm, backphrasing, flying free of the beat, emphasizes this feeling of floating, of magic.

Now, SZA’s songwriting isn’t much like the previous hundred years of Western pop music. We’re accustomed to discrete tunes based on simple ideas that often repeat, hopefully develop, and fall into clear sections. A verse might surge into a prechorus that leads to a contrasting chorus. Each new section might define its presence with a distinct sonic signature - perhaps longer or shorter note durations, perhaps a different pitch level. But SZA sounds like she’s just improvising over a looped instrumental. What’s going on?

I think we’d be foolish to conclude that SZA doesn’t know how to write a conventional pop song, that she can only freestyle. Her approach is simply an outgrowth of modern trends in pop music. For years, rappers have created long sections of music that don’t resemble traditional melodic songwriting. They’re rapping, not singing, and words without pitches inspire different structures. When Kid Cudi and Drake popularized rap-singing, they simply sang the way people had rapped, by developing melodic ideas in much the way they’d developed words, rhythms, and rhymes. SZA follows suit.

Today, a singer often comes into a studio and improvises ideas over an instrumental. Then, producers spend time reordering and shaping those ideas into verses and choruses. What SZA does resembles the first step without the second one. And yet there’s a structure to her music, in which melodic ideas repeat and develop. It’s just not a traditional pop structure. And I think it’s commercially acceptable because the way was paved by singing rappers like Drake. I also don’t believe that SZA simply improvises on a mic, then calls the result a finished song. She seems to have worked on “Good Days” for more than a year. She worked on her first album, Ctrl, for so long that finally the record label took her hard drive and finished it for her.

There’s nothing particularly “better” or “worse” about this word-heavy, less melodic approach to singing. It’s simply different. Art songs in classical music were often similarly less often based on catchy tunes, and more often the result of setting poetry to music. Perhaps a better analogy is recitative in older operas, in which characters sang dialogue rapidly, in the manner of speech, leaving melodic song to arias.

“All the Stars”

Rest assured that SZA can write killer tunes in the traditional mode as well. And she can carry her unjazz influences into a catchy chorus. Let’s look at the irresistible hook she sang in “All the Stars”, from the equally irresistible 2018 movie Black Panther. Here, we’ll see SZA apply her ability to levitate at the seventh scale degree and above to more conventional pop music.

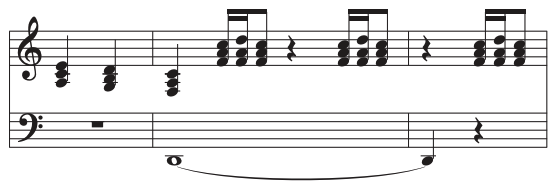

The instrumental, by Al Shux and Sounwave, includes a distinct bass throughout, but at first the treble lacks in clear pitches. Chords are implied, but barely - yet another example of our old friend, 🤷🏽♀️ harmonic ambiguity. During the choruses, a keyboard patch enters that finally brings the chords into focus. It’s yet another example of jazz harmonies without jazz stylings:

| A♭ | Fm | A♭M7 | Fm7 | Cm | Gm7 | Cm | B♭6 |

The hook SZA sings over this falls into two four-measure overlapping phrases. Here’s the first:

She with a rapid climb to the 9th scale degree on the B♭. It’s another example of climbing the ☰ ladder of thirds, this time from the 5th degree (E♭) to the 7th (G) to the 9th (B♭). In the first full measure, over the A♭, she heads back down to E♭, but with a strong emphasis on the F.

In the next measure, over the Fm chord, she does something quite extraordinary. She stacks thirds in the opposite direction, starting with a consonant note - F - and descending D - B♭ - G. This pleasant climb back down our ☰ ladder of thirds outlines a Gm7 chord. The only issue is that the harmony in this measure is F minor.

| F D B♭ G |

| Fm |

While the F is highly consonant here, the D, B♭, and G have no business over an F minor chord. Then, having 😎 established these dissonances as consonances, she feels free to repeat these notes over an A♭ chord, where the melodic notes are just as dissonant. Then she does it again over F minor, finally ending on a suddenly consonant C which foreshadows the upcoming C minor chord.

Let’s play those notes for you slowly, so the dissonances can sink in:

Let me remind you that SZA’s doing this not in an experimental indie recording, but in the lead single from a superhero movie. And yet, though it’s hugely dissonant, this tune sounds natural. What’s going on?

Well, certainly it’s an example of the power of the ☰ ladder of thirds - like we saw in part one in “No Scrubs”. Anchoring off the highly consonant F over an Fmi chord, SZA can descend by thirds to any notes she wants:

Next, now that she’s established these notes as acceptable, she uses the time-honored pop principle of ♻️ _ consonant once, consonant again_ to sing them over the A♭ chord, even though all four pitches are traditional dissonances there.

All that said, it helps that the keyboard patch in this first half of the chorus wipes out the pitch content of the original sample, which loosely implied the A♭ and Fm chords. And the only truly audible note in that patch is the top one:

| keys | E♭ | F | G | A♭ |

| bass | A♭ | F | A♭ | F |

These pitches fit more reasonably with SZA’s melody. Finally, again, modern production makes SZA’s voice so strong that it dominates the song’s pitch content. We have no choice but to believe she’s singing consonances.

In any case, I believe that these highly dissonant four measures are what give the next four measures their power. Overlapping with the end of the previous phrase, the new one goes like this:

The second phrase takes after the first phrase, recycling the same rhythm and using a similar melodic contour that features repeated descents in thirds. But now it’s strongly consonant. Picking up on the B♭ of the first phrase, the second phrase jumps right up to a high C, a super-strong arrival on the first scale degree of C minor. In measure 5, it moves gently down to B♭. In measure 6, 7, and 8, SZA descends D-B♭-G, outlining a G minor chord. This echoes the D-B♭-G of measures 2, 3, and 4, normalizing the previously dissonant tones as consonances.

While the first phrase’s chord progression is subtle, ambiguous, moving between A♭ and F minor, the second phrase’s chord progression is strong, deploying a i-v-i progression that establishes C minor as a tonal center. This may be why the arrival on C minor is so strong. It’s so consonant, such a relief from the extreme dissonance of the past three measures. Notably the arrival doesn’t occur through a gradual transition - it comes from a sudden leap up more than an octave.

We don’t have time to discuss SZA’s verse here, but you should give it a listen. We’ll just note that although it’s less adventurous than her solo work on songs like “Good Days,” you’ll notice some of the same melodic motifs. In particular, check out the C-B♭-F’s at the start of her verse, at 2:18 in the track. These should remind you of the repeated C#-B-F#’s she sang in “Good Days”.

As with the harmonic adventures of Drake, I don’t think what SZA does would be possible without modern production techniques. These make SZA’s voice so strong, so prominent in the mix, that she doesn’t need support from the accompaniment. She’s free to explore jazzy melodic tones without the harmonic underpinnings. She can create unjazz!

“Hit Different”

SZA’s other work features similar unjazz adventures. I was particularly struck by “Hit Different”, her 2020 collaboration with The Neptunes, Rob Bisel, and Ty Dolla Sign.

The track is quite sparse and loose, leaving SZA plenty of room to explore. The Neptunes’ instrumental is based on two stunningly 🤷🏽♀️ ambiguous chords. I can’t clearly make out all the pitches in each cluster, and the second chord’s bass is so low that it’s pretty indistinguishable. But the chords are something like this:

What are these clusters? The first is some flavor of a B♭13. The second chord might be a Cm11, but you really can’t hear the bass. You might just as easily hear it as an E♭M7 chord with some upper extensions. It doesn’t actually matter, and it probably didn’t matter to SZA. Like Drake, I imagine she heard a tonally ambiguous instrumental and picked out a scale that matched it, in this case, an E♭ major scale.

As usual, SZA’s verse bears little resemblance to a traditional pop melody. Here’s how it starts, at 0:37 in the track:

| C G E♭ C A♭ | G A♭ B♭ F D C E♭ C B♭ | E♭ C A♭ F |

| B♭13 | Cm11 | B♭13 |

Starting on the C, the 9th scale degree, she jumps up to a G (the 13th scale degree), then walks down the ☰ ladder of thirds to the 11th (E♭), 9th (C), and 7th (A♭) before coming to a rest on the low G, which is now consonant over the Cmi. Then she leaps up to the F, a dissonant 11th, gradually resolving this to a consonant E♭, then meandering down to C and B♭ before returning to E♭ over the B♭ chord, where it’s now a dissonant 11th. She once again descends the ☰ ladder of thirds down to the 9th (C) and 7th (A♭), this time continuing the progression down to the 5th (an F at the bottom of her range).

Coupled with her rapid, speech-like rhythms, this is highly complex. But behind the surface density, SZA’s melody prolongs a quite logical progression from G down to F and E♭. You can hear this if I play the original tune while emphasizing the dominant pitches, which I’ve helpfully included in this chart:

| G | G F E♭ | E♭ F |

| B♭13 | Cm11 | B♭13 |

This phrase goes on with a flurry of notes that then blend smoothly into a quasi-repetition. We could spend all day on this song, and we probably should, but we really need to move on!

As I listened to SZA’s music and read and watched her interviews, I was reminded of Steve Nicks, another woman who set evocative lyrics to meandering, nontraditional melodies. The difference is, Stevie lived in an era where the verse- chorus structure was king, and she had collaborators like Lindsey Buckingham to help impose structure on her work. Still, if you listen to songs like “Dreams” and “Gypsy”, you’ll hear a similar approach, with improvised-sounding, wide-ranging melodies that stay within a scale but don’t seem especially attached to the harmonies they exist over, resulting in unresolved dissonances.

In a comment on a SZA interview on YouTube, someone said, “She’s truly a fairy princess with an abundant fro and spirit slathered in tie dye.” Take away the tie dye, and couldn’t that apply to Stevie Nicks?

Unjazz today

Kid Cudi, Drake, Rihanna, SZA, and other pioneers opened up the unjazz floodgates. Today, if you check out the top streamed songs on Spotify, you’ll hear a mix of harmonic styles. Some songs use chords and melodies drawn from traditional rock or pop. Others use funk-influenced jazz harmonies. And sometimes you’ll hear blissfully experimental unjazz!

Of course, many singing rappers and R&B singers write melodies that are completely traditional. I’ve written about how Lil Nas X, in “Old Town Road”, did the reverse of what I’m talking about here. Instead of destabilizing harmonies with unjazz melodies, he wrote a melody that harmonically strengthened and unified a tonally ambiguous instrumental. Travis Scott did something similar in ”Goosebumps”, where his highly tonal, conventional melody helps normalize one of the weirdest instrumentals to ever hit 1,450,395,526 streams on Spotify.

But unjazz has seeped into the top 40 nonetheless! Let’s look at two recent examples.

“Streets”

Doja Cat’s 2019 song ”Streets” is built on a sample that uses the E minor scale, sparse drums, and a thick, very low bass. The bass plays the note C, then slides down to a B that’s so low it only vaguely implies any sense of pitch. In the third bar, the bass moves up to E. In the third beat of the fourth bar, it returns to that very low B-like note, which sounds almost exactly like the original C, obscuring our sense of downbeat. When played on a piano (ok, a piano sound with a bass that I can slide down a half-step), the whole thing sounds like this:

No section clearly plays the role of a chorus. If I were forced to choose, I’d pick the first vocal section, at 0:32 in the track, as it’s vocally simple, repeating the words “like you.” This could have even been the song’s title, if it wasn’t already named “Streets” after the opening sample, from B2K “Streets is Callin'”.

At 0:52, the music intensifies slightly as a faster vocal line is introduced. The vocal harmonies are diffuse and a bit hard to make out, but go something like this, mostly in parallel fifths:

The top line emphasizes the note F#, returning to it on every downbeat. Over the E minor, this F# is a 2nd or 9th, a traditional dissonance, but a frequent unjazz consonance. But before we hear the F# over the E minor chord, we hear it over a C. There, not only is the F# an even more dissonant tritone, but it’s reinforced by the equally dissonant B in the harmony. This is another example where ♻️ a melody that’s consonant over one chord is then treated as consonant in a context would it normally be dissonant - except that the dissonant chord occurs first, and the dissonance is justified after the fact. The parallel fifths in the harmony introduce further dissonances, but it’s all good as long as we ⚖️ stick with the same scale throughout.

Once again, the track lacks any extended jazz harmonies that would help reinforce F# as a consonance. The main sample helps a little by expressing prominent neighbor-tone F#. But in the world of unjazz, 😎 📈 this prolonged 9th can be a consonance without explicit harmonic support.

The song’s next section, at 1:15 in the track, feels to me like a verse. It even features our first proper tune. (In this diagram, I’ll put the low, ambiguous bass notes in parentheses.)

| G F# E D B | G F# E D E | G F# E D B | B E B F# G |

| C | C (B) | Em | Em (B/C) |

Looking at this on the page, it resembles a more traditional melody. You can loosely trace a journey from the consonant G at the start down through a passing F# to the E in the fourth measure, like this:

[play G F# over a C chord resolving to E over Emi]

But if you listen to the tune, you’ll notice that it actually continues to emphasize the F# that the previous section prolonged. The opening G feels more like an upper neighbor to the F#, which then descends down our good old ☰ ladder of thirds, from the sharp 11th (F#) down to D (9th) and B (major 7th). Over the E minor chord, this happens again, with the F# and D now playing the roles of 9th and 7th. Then the melody rises right back up to F#. So although it’s possible to hear this tune in a way that makes the F# a passing note, I think that F# really serves as the main pitch - even though it’s a tritone over the C.

At 2:17, there’s a quasi-sung rap middle section. Even this section repeatedly emphasizes the note F#. The whole song emphasizes this note, a wonderful unjazz 9th scale degree.

“Montero”

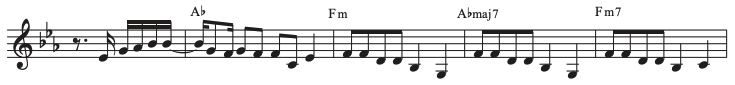

Let us close with a quick look at a song that came out as I was writing this piece: Lil Nas X’s “Montero”. Here’s the song’s first melody, right at the beginning (this song doesn’t really have verses and choruses, either):

| A♭ | A♭ E♭ D♭ C♭ | D♭ A♭ | A♭ E♭ D♭ C♭ | D♭ |

| E♭ | F♭ | F♭ | E♭ |

It’s a simple tune consisting of two melodically identical phrases. It would be quite conventional and consonant over different chords. For example, here’s how it would sound over an A♭m - D♭m progression:

But wouldn’t that be boring? Instead, it occurs over an E♭-F♭ progression, where it forms a cluster of gratuitous unresolved dissonances. For example:- the opening A♭ over the E♭ chord. This highly dissonant 4th doesn’t pretend to resolve to a neighboring 3rd or 5th. It’s just dissonant, and 😎 after a while we get used to it. When the first phrase repeats, that A♭ becomes a consonant 3rd over an F♭ chord. Like in “Streets,” ♻️ a melodic phrase that’s consonant over one chord can be reused over a chord where it’s dissonant - except that, once again, the dissonance comes first, and its justification comes second.

- the D♭ that ends each phrase. This D♭ kind of makes sense as a 6th over the F♭ chord, and also kind of makes sense as a 7th over the E♭ chord. Normally these 6ths and 7ths would be reinforced by the context of other extended pitches or jazz chords. But this is unjazz. We don’t need that anymore.

In a larger sense, Nas X is just 🖕🏾 singing the “wrong” scale, choosing a scale that he likes and ⚖️ sticking with it without regard to individual chords, knowing that the scale will fit the harmonies macroscopically.

At 0:16, the rhythm kicks in, accompanied by a new melody:

| E♭ | A♭ B♭ C♭ B♭ | E♭ D♭ C♭ E♭ | A♭ B♭ C♭ B♭ | E♭ D♭ C♭ |

| E♭ | F♭ | F♭ | E♭ |

The first phrase begins by rising from E♭ to the dissonant A♭ we heard in the first section. This time, the A♭ resolves up to B♭ - conventional dissonance treatment at last! In the second measure, the phrase ends by falling down to a C♭, a nice consonant 5th. But then, using ♻️ consonant once, consonant again, the whole phrase repeats over a F♭ and E♭ chord, ending once again on that C♭, which is now a completely dissonant and utterly unresolved 6th. Nas X could have changed the tune to go down to a consonant B♭. But he didn’t bother. He didn’t have to. This expanded approach to dissonance is now part of the language. If we’ve listened to the last decade of Drake, Rihanna, and SZA, our ears have been trained to accept this.

To me, this C♭ is one of the strongest pieces of evidence we have that unjazz exists - that these melodic choices are made deliberately, not by accident by people who somehow cannot sing logical melodies. I mean, “Montero” is a followup to one of the most successful singles of all time. If Nas X had somehow been incompetent enough to sing a glaring dissonance, surely his producers would have Autotuned it down to B♭. Unjazz was the goal.

Besides, it’s not like Nas X can’t write a traditional tune. Have you heard “Old Town Road”?

Rappers are good singers

Some people like to say that rappers can’t sing. I think this is nonsense. After all - what is “singing”? It’s using your voice in a way that appeals to an audience, that makes a song emotionally effective in a given cultural context. Sometimes we want to hear a highly trained singer perform ”Un bel di”. But other circumstances call for someone who’s self-taught. In pop music, the singer who’s rough around the edges is often more interesting, charming, and effective. If this song had been sung by an opera singer, I would never have heard of it. This is the case in rock and hip-hop alike.

For people who fear that pop music has gone stale, that it was better when you were thirteen, or that the rise of single-progression songs has hampered creativity - fear not! A group of adventurous R&B singers, rappers, beatmakers, and producers have been exploring complex rhythms and harmonies the likes of which have rarely been heard in American popular music. While pop and rock performers continue to mine the past, R&B and hip-hop artists have widened what’s harmonically possible. It’s especially remarkable that they’ve done so while continuing to create songs over repeated instrumental patterns.

The beatmakers and producers have realized that surprising sounds and dissonances can be catchy when paired with drums. And singers and rappers, secure in the knowledge that Autotune and modern production will make their voices sound big and secure even with no harmonic support for their dissonances, they boldly sing melodies in a scale and key that vaguely fits an ambiguous instrumental - then sounds correct by force of its sheer volume and space in the mix.

I regret that this article got so long. I kept discovering music that amazed me, and I had to take apart each song to see what made it tick. I also regret that I didn’t spend more time talking about modern R&B singers, since their adventurism continues to astound me. Have you heard H.E.R.’s “We Made It”? If not, will you please give it a listen?

Welcome… to unjazz!