When a piece of music sets up expectations, then fulfills them, I believe it deepens the experience. It engages a mind’s rational and emotional components in a new way. The music, the notes themselves, tell a story!

Of course, a piece of music can be highly effective without any tension and release whatsoever. But, for me, this technique opens a door that can carry the music into the realm of higher art. And the composer doesn’t need to be a music theorist to do it, or even be able to read music. They might just hear the verse they’re working with - really hear it - and realize it would be satisfying to follow it by a chorus that highlighted just the right pitch or harmony.

But what happens if a song sets up strong expectations and then completely ignores the consequences? Music can do whatever it wants. But - this? A story with a setup and no end? It seems perverse!

Now let me tell you why the new Imagine Dragons song, while it’s compelling, drives me completely nuts. And then how Lin-Manuel Miranda used similar harmonic materials to create a song that I found more satisfying.

“Enemy”

I’m talking about Imagine Dragons’ song “Enemy”, featuring a guest bridge from JID, from the new Netflix series “Arcane: League of Legends”. Listening to this song, I kept feeling like it was incomplete, unsatisfying, as I waited for it to go somewhere that it would not. Like it was setting up an expectation that it cruelly never fulfilled.

The song

First, let’s summarize the song. It’s built on a progression that repeats an unusual pair of chords: G and F.

| G | F |

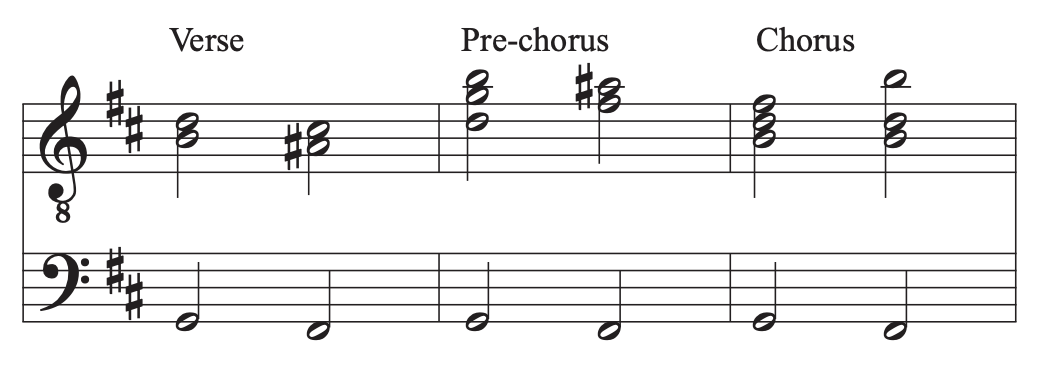

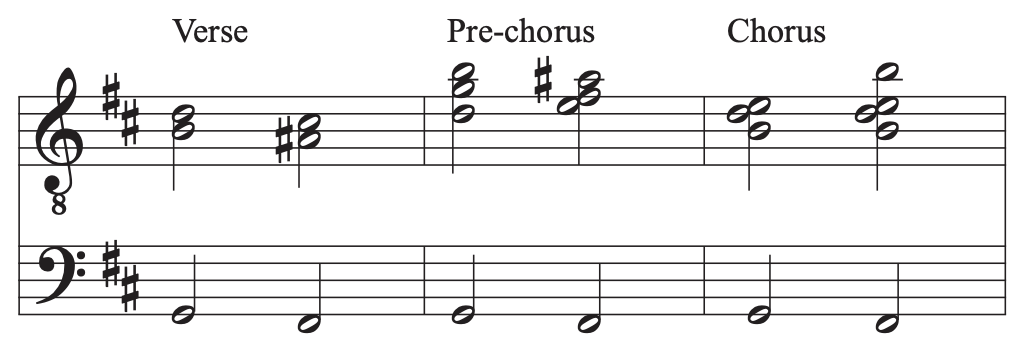

Each of the song’s three main sections repeats its own simple melodic phrase over the chords. Here they are:

Verse:

| B D B | A C A |

| G | F |

Pre-Chorus:

| B A G D | F E | B A G D | F A |

| G | F | G | F |

Chorus:

| E F E D B | E D B | E F E D B | E D B D |

| G | F | G | F |

What key is this song in?

As we’ve discussed before, a pop song doesn’t have to be definitively in a certain key. Often a song reflects different key areas simultaneously. It may veer towards one key area and then toward another without ever definitively establishing one as primary. This is not a defect in pop music - it’s more of a characteristic treatment of the idea of tonality. Sometimes it makes the most sense to say a song is “in” a certain progression.

But I think it’s still useful to explore possible keys a song could be in. Doing so, we can learn a lot about how the music works, even if we don’t (and shouldn’t) arrive at an unequivocal conclusion. So let’s do that, keeping in mind that our goal is not to decide what key “Enemy” is in, but simply to hear it from different perspectives and better understand the music.

Isn’t it just in G?

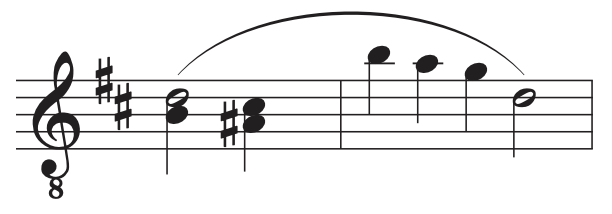

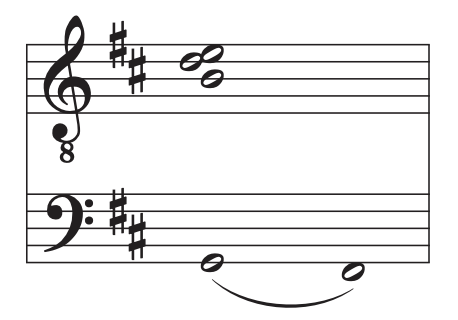

Naively we might say, hey, the first chord in the song is a G. So maybe it’s in the key of G! The first chord is indeed quite forceful:

But, right after that, we hear an equally assertive F chord.

That’s not something we normally associate with the key of G, so now we’re on uncertain tonal ground.

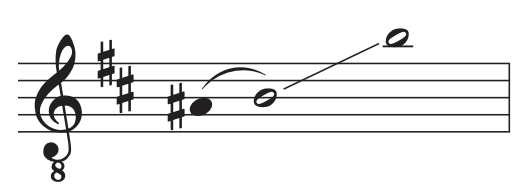

This brief introduction kicks off the verse. At first, the key-of-G argument looks promising once again, as Dan Reynolds sings a melodic phrase consisting solely of the notes D and B over a G chord. Those are the fifth and third scale degrees of G major, placing the first measure solidly in G:

| D B |

| G |

But, in the second measure, the F chord returns, inspiring Dan to sing C and A, the fifth and third scale degrees of F major. It’s just as firmly in F as the first measure was in G.

| C A |

| F |

If the second chord was, say, D instead of G, we could make a reasonable case for the key of G, as D is the V chord of G. But the second chord is F, and that chord can’t enter the key of G without a passport. Its A is deeply foreign to the G major scale. Every G chord in the song is followed by this inconvenient F, and each time that happens, the F weakens the case for the key of G.

If the melody happened to imply the key of G during every F chord, we’d feel a little more like we were in G. But the melody in the second measure includes a clear A, which negates G major. What’s worse, this A is prominent at the end of the pre-chorus as well.

The only section whose melody helps make the case for the key of G is the chorus. Here, the melody over the F chords uses the notes B, D, and E. These pitches are quite characteristic of the key of G, particularly the B and D, the third and fifth scale degrees, which feature prominently over the G chord in every section. You can hear the impression this makes by playing E, D, and B over a G major chord, then over an F major chord:

| B D E | B D E |

| G | F |

It’s a bit of evidence for the key of G, but it’s pretty weak. In fact, later on we’ll see that these pitches are even stronger evidence for… something else.

It would help if the melody ever descended to a G, the first scale degree, the way the melody descends to the first scale degree so often in, say, “Say It Ain’t So,” or in so many Vampire Weekend songs. But it doesn’t. No dice.

Then is it in F?

If the song isn’t convincingly in the key of G, what key is it in? Perhaps it’s in the key of the song’s only other chord: F. Maybe, in all those G-F progressions, those G chords are ultimately resolving down to the F. If you listen just right, you can hear that G gently sink down into an F:

| G | F |

Unfortunately, “Enemy” doesn’t do much to help us hear the progression this way. To start with, at no point is there a convincing resolution to F. A G-F cadence is not remotely as satisfying as, say, C-F - a nice V-I cadence. Or even, closer to the song’s actual chords, a Bmi-F, which would be a iv-I quasi-plagal cadence.

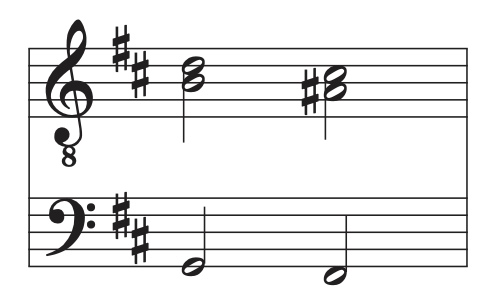

| C | F | Bm | F |

| V | I | iv | I |

When you hear a G-F progression, featuring the pitches used most often in the song, don’t you feel like it’s not fully resolved? Like it wants to end up on some third chord? Listen to this, and imagine what chord you might expect to come next. (We’ll give you the answer below.)

| B D | A C |

| G | F |

The pre-chorus is the one section where the melody helps us feel a cadence in F, if only just a little. In this section, the melody descends twice to F, the first scale degree of F. In the first two measures, the tune goes B-A-G-F, with only a small break to dip down from G to D:

| B A G D | F E |

| G | F |

The way we land on F makes it feel more like the song’s visiting an F tonality of some sort. But it’s not a terribly strong landing. The B-A-G happens over a G chord, and it’s in the scale of G major, which feels like a small landing on G. When we get to F, we only stay for a moment. And then, in the second half of the pre-chorus, the melody’s descent to F is followed immediately by a strong jump up to A - an A that yearns to go somewhere else. (But where? where?)

| B A G D | F A |

| G | F |

Besides, Dan sings these vocals in falsetto. The prechorus is built to feel like a transition, which is of course what it is. In other words, I’m not really feeling F here.

At this point, we’re out of options. Iit would be reasonable to would be to say this song is simply “in” a G-F progression. But before we settle on that, let’s look at one more aspect of the song: the scale used by the song’s melody.

Let’s look at the scale

Assembling all the pitches in the song and sorting them from lowest to highest, we get the following scale:

G A A B C D E F

It doesn’t look much like a G scale. Take out the A, and it’s a G Lydian. But the A is quite prominent in this song, and we don’t want to omit it. So I don’t think this scale makes a good case for the key of G.

Let’s start instead with an F and see if the result resembles an F scale:

F G A A B C D E

Without the A, it could be an F Phrygian - but once again the A gets in the way.

We’d have the same problem trying to interpret this as a D scale. Can any scale commonly used in Western pop music logically incorporate A, A, and B - three pitches that are separated by semitones?

What if it were a B scale of some sort? Then we’d have

B C D E F G A A

B minor, really?

Suddenly, everything falls into place. A melody in a good old-fashioned B minor scale would frequently feature both an A♮ and A - typically, an A while rising and an A♮ when going down. “Enemy” uses the A♮ over the G chord and the A over the F chord. But frequently the accidental does correspond to the melody’s direction, as in the pre-chorus:

| B A♮ G D ⬇️ | F E | B A♮ G D ⬇️ | F A ⬆️ |

| G | F | G | F |

Doesn’t this make you think - although there are no B chords in this song, what if the song was actually in B minor? What if the melody’s prominent A’s yearned to resolve upward to B’s in a classic 7-8 melodic cadence?

At least one other writer has claimed the song is in B minor. While this choice may seem odd, the melody supports it strongly.

First of all, the highest note in the song is a B. The lowest note is the A an octave below. But that low A only appears once, in the verse, while the adjacent B is used a few times, particularly in the chorus. As the chorus is a section where large-scale dissonances often resolve, it’s not outlandish to imagine the low A hanging in our ears from the verse to a resolution to B in the chorus. Think of it like this:

The fact that the melody ranges from lowish B to high B doesn’t prove the song is in the key of B. But we do feel these B’s prolonged over the long term, that the B’s form the borders of the melody, and this effect strengthens our feeling that B is central to the song.

You can hear this if I play a quick summary of the song, sustaining the low and high B’s:

But to really examine how A resolves to B during the course of the music, we need to do a bit of melodic analysis. We’ll be loosely inspired by a bit of classical music theory called Schenkerian analysis, a system that aspires to rigorously organize a piece of music’s pitch content into a hierarchy. Schenkerian analysis has always been controversial, once because many people thought it was silly to reduce a piece of music to a few pitches, and now because people are pointing out the guy was a German nationalist (though a Jewish man who died in 1935) who would have rejected a whole lot of the world’s excellent music, then and now.

I’m not here to defend Schenker or condemn him, but I do think the general idea of melodic analysis is incredibly useful, particularly in pop music, where melody is often so prominent, and where a song often contains so few pitches, used so repetitively and consistently. But we’ll treat this idea loosely here, as I think it always should be. We’ll going to use some elementary techniques that show how we can “hear” a pitch not just when it’s played, but during the time after. And, again without any attempt at rigor, how a progression of pitches can underlie whole sections of music or even an entire piece.

We’ll do this work because it will tell us why I found this song so unsatisfying - why I felt like it set up an expectation it never fulfilled. Indeed, I was waiting for the repeated G-F chords to resolve to a satisfying B minor. This article is really my effort to explore the theory that informs the intuition.

The pitches, and the unrequited yearning for B minor

The verse

Let’s start with the pitches in the verse. Remember the verse?

| B D B | A C A |

| G | F |

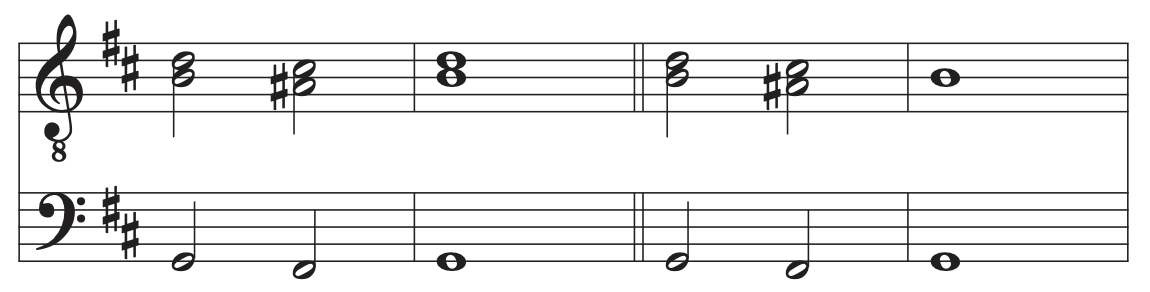

The melody uses two pitches over each chord. Of course these aren’t heard simultaneously, because Dan can only sing one note at a time. But, as it processes the melody’s pitch content, our brain conceptualizes the notes together. We can express this by verticalizing them - by writing the pairs of pitches as chords.

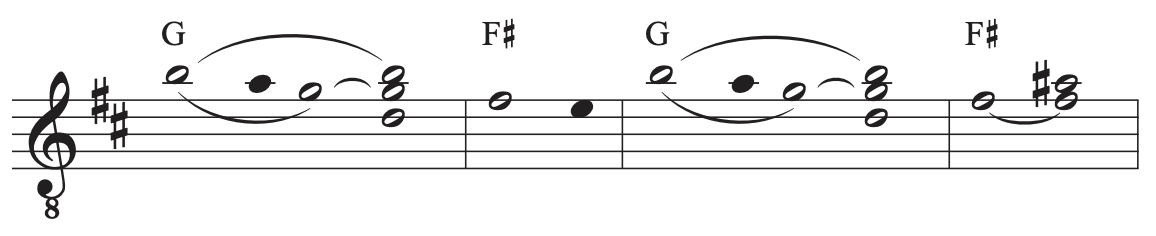

These chords show how powerfully the melody wants to resolve back to a B and D - or simply a B. Let’s hear those two resolutions:

Wouldn’t it be more satisfying if that resolution occurred over a B minor chord?

The pre-chorus

| B A G D | F E |

| G | F |

At the start of the pre-chorus, the melody does in fact resolve to a B and D… sort of. The first note is a B, but an octave higher.

This technique is common. We call it octave displacement. It lets a dissonant melodic tone resolve to the right pitch-class - just not to the right pitch. The tune jumps up an octave, raising the tension and avoiding a true cadence.

The melody resolves to D as well, but much more weakly, as it takes four notes to get there. You can imagine hearing the D persisting from the verse to the pre-chorus, like this:

But in actual life the connection is tenuous, partly because the B-A-G-D melody really centers around the note G, which is the first scale degree of the underlying G chord, and partly because it takes quite a while to get all the way down to D.

Speaking of G chords, let’s play the prechorus melody, but faster, while sustaining and giving more weight to chord tones.

Eliminating the passing note A, then verticalizing, we see that this tune outlines two progressions between G chords and partial F7 chords.

Let’s combine those into one:

Comparing those two chords to the prechorus melody, you hear that the melody sounds like those chords.

Notice how closely this resembles the B-D - A-C progression that defined the verse. The melody does explore a new area in the G and F chords - the notes G and F themselves. But it continues the B-A melody, just up an octave. How about the D-C? Well, Rubin must have wanted it to persist. If you listen to the pre-chorus closely, you can hear heavily processed backing vocals singing almost the exact same pitches as the verse (though not always in the same order):

| B D E | C A | B D E | C |

| G | F | G | F |

It’s just like the verse!

The verse yearned for a resolution to B minor. The pre-chorus jacks the B-A dissonance up an octave, adds a seventh to the F chord, and closes in a dramatic leap up to A over an F chord. It’s screaming out for B minor!

Chorus

| E F E D B | E D B | E F E D B | E D B D |

| G | F | G | F |

But, no. The chorus denies this desire, again… mostly. Notice that the notes of the B minor triad are always present over the first chord:

| E F E D B |

| G |

as well as the second chord:

| E D B |

| F |

Every measure of the chorus contains a B, D, and F, without the harmony ever touching B minor.

What’s more, the F chord in the chorus is defined weakly. The only clear indicator is the hit on A at the start of the measure. Aside from that, the only clearly audible pitched material is the melody. The A rings in our ears, defining the harmony as F, but if you’re able to forget it, the only clear pitches afterward are B, D, and F. It’s so close to B minor.

I might verticalize the chords like this:

That reflects a more traditional viewpoint in which the E is a dissonance, an incomplete neighbor to the D or a passing tone. But, listening with pop ears, it’s pretty easy to also hear it this way:

The chorus melody’s low note and high note are both B. That range, plus our first interpretation of the other pitches, brings us about as close as you can come to saying, “We’re in B minor!” without actually being in B minor.

Oh, and if you miss the B-A alternation that characterized the verse and pre-chorus, check out the single-note hits at the start of each measure:

| B | A | B | A |

| G | F | G | F |

Don’t you just want to hear it resolving?

| B | A | B |

| G | F | B |

We’ve found the key notes in each section of the song. Putting them together, we can see the whole thing, along with the quasi-resolution to B minor in the chorus. I want to repeat the disclaimer that this is very little like real Schenkerian analysis. But I think the reduction we’ve done makes sense. These two diagrams summarize different interpretations we’ve come up with. Don’t these sound like the pitch content of the song? Which is your favorite?

It drove me nuts

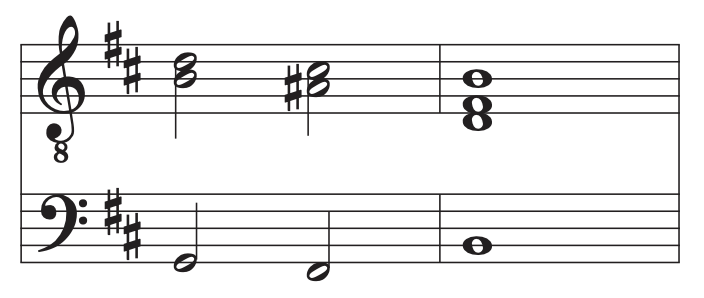

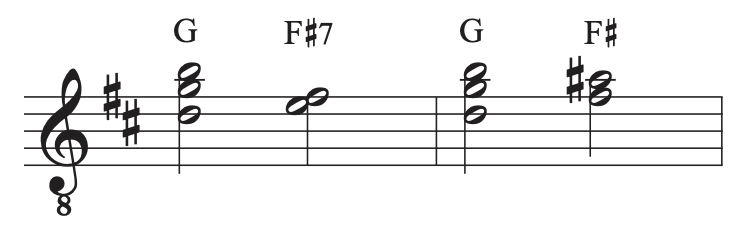

This is why the song drove me nuts! The G-F just yearns to be the VI-V of a lovely VI-V-i progression:

| G | F | Bm |

| VI | V | i |

Just imagine if the prechorus was in that key. Or the chorus! Wouldn’t this be satisfying?

Okay, my version sounds dreadful. But I’m convinced that more thought would yield an awesome chorus in B minor. To my consternation, in real life, this satisfying chorus never happened.

So, what key is it in?

So is this song really in B minor? My strong opinion is: it’s a matter of opinion. This table is my final word on the subject - because, again, sometimes the only point of exploring what key a song is in is in finding different lenses through which to interpret the song, to learn more about it.

| Key | Pros | Cons |

| G | First chord of the song. The melody over each G chord is based on chord pitches. | Nothing else really establishes G as a key area. |

| F | Each G chord is followed by an F. | Nothing else really establishes F as a key area. |

| B minor | The entire song yearns to go to B minor. The G and F feel like VI and V chords. The melody uses the B minor scale. In the chorus, we almost resolve to B minor. | There’s no B minor chord in the song! |

We do talk about “Bruno”

Now let’s look at a song that sets up the same expectation, but actually satisfies it: “We Don’t Talk About Bruno,” the hit song from the movie Encanto. It’s that rarest of animals - a theater song that’s a #1 hit!

A hope fulfilled

“Bruno” was written by Lin-Manuel Miranda, a musical theater songwriter, the kind of person who finds it natural to write songs that aren’t based around a single chord progression.

The song begins with what we’ll call its refrain: the part with the lyrics, “We don’t talk about Bruno.”

| E♭ A♭ E♭ A♭ E♭ | D B G F G | E♭ B♭ E♭ C E♭ | F D |

| A♭ | G | A♭ | G |

Like in “Enemy,” the first two chords are major triads a half-step apart. Also like in “Enemy,” the melody over each chord is built around the chord tones. You can hear the connection if we play a compressed version of the first two bars of “Bruno”, then a quick version of the first two bars of “Enemy” transposed to the same key:

Thus, just like in “Enemy,” the A♭ and G chords in the first two bars of “Bruno” feel like the VI and V of C minor. The third and fourth bars repeat the A♭ and G chords. But the melody in bar 4 shifts upward to an F, the seventh scale degree, and the piano plays a repeated G7 chord. Repeating the chords builds suspense, and adding the seventh further fuels the drive toward C minor. The listener is poised for the song to go there!

And then - satisfaction! Unlike “Enemy,” “Bruno” fulfills the expectation it sets up. The refrain resolves gloriously to a verse-like section that’s in C minor, revealing the key of the song. Yes, this song firmly establishes the key of C minor, and this is how.

| Refrain | Pepa and Félix duet | |||

| E♭ A♭ E♭ A♭ E♭ | D B G F G | E♭ B♭ E♭ C E♭ | F D | G E♭ G E♭ |

| A♭ | G | A♭ | G | Cmi Fm |

Doesn’t it feel satisfying when an expectation is set up and then fulfilled? And the chord that resolves the tension also begins a new section of the song, the Pepa and Félix duet. That section is based on a harmonically stable groove, but it carries along the energy from that tension and release. It’s like, with the refrain, the listener glides down a ramp, and when the duet starts, the listener’s sailing through the air, standing still, yet flying along.

Miranda redeploys the A♭-G progression for this purpose whenever he needs to kick things up a notch. We just mentioned that the duet is based on a repeating chord progression. But, after three times through the chord progression, at 0:241, the song returns to the A♭-G and suddenly gets louder, as Pépa sings, “You telling this story or am I?”

A big retransition

The same trick is used in the grand retransition from Isabela and Dolores’ contrasting middle section at 1:52. Another loud A♭-G moment finishes in a deceptive cadence, as this section starts by shifting into a pastoral E♭ major.

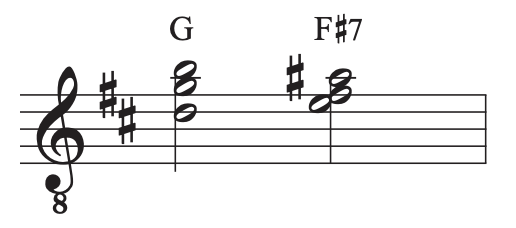

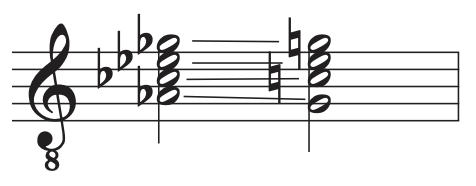

Then, at 2:30, Miranda deploys the A♭-G progression in double time, not just once, but four times in a row:

| A♭ G | A♭ G | A♭ G | A♭ G |

When the chords happen twice as quickly, the song intensifies. When they repeat four times, it intensifies further. We’re aching for a return to C minor! But, gloriously, instead of giving us that, Miranda prolongs the tension by shifting course to a surprising A♭m7 chord. There, we wait breathlessly for two bars before we finally do return to C minor for the big climax: the virtuosic ensemble section which ends the song. The whole thing sounds like this:

| A♭ G | A♭ G | A♭ G | A♭ G | A♭m7 | A♭m7 | Cmi |

This A♭m7 is a highly inspired moment, and wonderfully not one that I know how to analyze with classical harmony. It’s a bit like an augmented sixth chord. I mean, in classical European harmony, you can build a seventh chord on the sixth scale degree, then resolve that to the tonic via V. The seventh scale degree of the VI chord is then considered not as a seventh, but an augmented sixth, because it resolves up, not down. Like this:

But an augmented sixth chord would resemble an A♭ dominant seventh. Miranda uses a minor seventh. To me, the minor makes it sound even more distinctly A♭-like, further from C minor. After all, the scales used in C minor and A♭ major differ only by a single note, but A♭ minor is in a harmonic world of its own. Instead of approaching Cmi by following the A♭ chord with a G chord, Miranda ventures to the most harmonically distant region of the entire song, and then abruptly shifts us back to C minor.

Of course, if you look at the A♭m7 and Cm, one resolves to the other quite logically through contrapuntal motion:

Perhaps the Cb is useful because it’s enharmonically equivalent to B, which is the leading tone of C, and which would occur in the G chord that’s missing here. A G chord would be what you’d expect. It’s the V of C minor, and it’s how we’ve gotten to C minor so far in this song. But this is why you should write with a creative ear, not with theory! If the A♭m7 was in fact followed by a G, it would be so anticlimactic:

So, the A♭m7 is surprising, and I have no idea how Miranda came up with it as a way to return to C minor, but I think it sounds fabulous. I can’t wait for the opportunity to steal this trick myself.

Analysis gives you sight; theory makes you blind

Sometimes, your song needs something, but you don’t know what. Analysis can teach you what your song is actually doing, and thus what it still needs to do. It lets you take a step back and get a fresh perspective on your music, away from the emotions that may have inspired the song and the emotions that are bound up in the creative act. It’s an opportunity to be objective, to be your own editor.

Analysis requires theory. Before you can analyze, you need to know theory. But while you’re writing, while you’re being inspired, you want to leave theory somewhere in the back of your intuition, so you can let your ear guide you. How else would Lin-Manuel Miranda come up with the marvelous A♭m7 that he indulges in for two bars before his final return to C minor? Theory would have told him this was impossible.

Why doesn’t “Enemy” ever satisfy us by moving to B minor? Well, the Imagine Dragons songs I know are all based on a single chord progression. That’s why I imagine (get it?) that, during the creation of “Enemy”, the band members, and even their great producer Rick Rubin, never considered migrating to B minor as the music cries out to do.

Still, I wish they had! I think this would have made this catchy song more satisfying, more deep. If the band didn’t want to use a new chord in the verse, pre-chorus, or chorus, they could have done it in the bridge. Imagine how satisfying it would have felt, after waiting two minutes, for the band to introduce a bridge in B minor. (Actually, though, I wouldn’t want to change the current bridge, since that’s JID’s rap, and his virtuosic performance is by far my favorite thing in the song.)

Don’t get me wrong. Although I’m biased toward chordier music, plenty of fine songs are built on a single, repeated chord progression. You can create plenty of motion and variation within this form’s confines. Just check out “Smells Like Teen Spirit”, “Firework”, or “Blinding Lights”. And there’s no point in Imagine Dragons hits like “Radioactive” or “Believer” where I’m crying out for a new chord. They’re satisfying just as they are. It’s just… “Enemy”.

This article explored the power of the VI-V-i progression in different styles of pop music. But this progression is not new. It originated in European classical music. I’d like to close with a dramatic example - a composition that repeats this progression again and again, reveling in its awesome, tragic majesty. Behold - Rachmaninoff!

I use timecodes that correspond to the song track itself, not the video, which has a short intro that’s cut from the single. ↩︎