A little while ago, people on the excellent Indiepop Shop Talk Facebook group discussed songs that rise by a half step for the final chorus. Arguably, this is often an egregious, cheap trick that's extraneous to the song - but it can also be done in a way that's wondrous and completely organic! I'm thinking now about the Nelson Riddle/Frank Sinatra Strangers in the Night, which rises at the end by a full step, or My Heart Will Go On, which jumps up an astonishing major third - that making it a song I can stand to listen to as I look forward to that gravity-defying upwards leap. And I really want to talk about those songs! But this post isn't about them. This post is about a similar topic - those rare and wondrous songs where the verse and chorus are each in a different key.

The verse and the chorus in different keys - what a bold idea! We're used to - or at least before the 1990s we used to be used to - bridges that travel to foreign key lands. But, doing it in the chorus, in the second section of the song? That takes guts! Changing keys thirty seconds into a song risks confusing the listener, losing the thread of the music; you have to be really careful that the listener knows you're still in the same song. It's not so hard to have, say, a verse in a minor key and a chorus in the relative major - like, E minor and G major. But - say - a verse in C major and a chorus in D major? Not easy. And then you have to get back to C for the next verse!

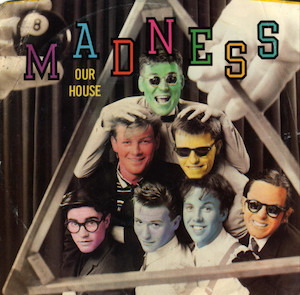

I've always thought one particularly smooth example of a song with a verse in C and a chorus in D is Let's Hear It for the Boy, which took the idea of a new key for the chorus all the way to #1 back in 1984. Then there's Jump for My Love, from the same era, which arguably is only memorable for its similar full-step modulation to the chorus (and a great performance in the video!). But this post isn't about those songs. This is about another song that toggles between C to D from the same era, by Madness - "Our House".

Here's the song on youtube. The song's verse begins conventionally enough, with four repetitions of the chords C-Gm-Dm-Fm. But then, shockingly, only a few seconds later, the chorus comes in with an abrupt shift to the same progression transposed to D. The second verse shifts back abruptly to C. The second chorus goes to D, and then, shockingly and beautifully, shifts to yet a third chord area, B. And yet it feels so smooth… so natural… what's going on here?

As with all good things in music, this song strikes a clever balance between continuity and discontinuity, between the expected and the pleasant surprise. And, ultimately, it's all about a little pitch called F#. But - how?

The music

First of all, let's chart out the song. Here are all the pitches used in the verse:

| D C D C D E | G | F E D E | F E D E | D C D C D E | G | F E D E | F C D C |

| C | Gm | Dm | Fm | C | Gm | Dm | Fm |

and the chorus:

| F# E | E F# G F# E F# | D F# E | E F# G F# E F# |

| D Am | Em Gm | D Am | Em Gm |

Now, on to the chords. The song's basic chord progression is C Gm Dm Fm. When those four chords happen once, we'll notate it like this:

| C | (1x) |

indicating the cycle has occurred once in the key of C. Twice in a row, as in C Gm Dm Fm C Gm Dm Fm, we'll notate as

| C | (2x) |

Here's the exact same progression transposed up a step to D:

| D | Am | Em | Gm |

and down a half-step to B:

| B | F#m | C#m | Em |

Those are the building blocks of the whole song; aside from a transitional bit before the instrumental section, the song consists of repetitions of those chord sequences, though the chords in the chorus occur in double time.

Here's the song using that notation:

| Verse 1 | C | (4x) |

| Chorus 1 | D | (2x) |

| Verse 2 | C | (4x) |

| Chorus 2 | D (2x), B (2x) | |

| Verse 3 | C | (4x) |

| Pre-solo instrumental bit | G | |

| Instrumental | C | (4x) |

| Chorus 3 | D | (2x) |

| Retransitional tune over Verse chords | C | (2x) |

| Verse 4 | C | (4x) |

| Chorus 4 in D (2x), B (2x), C (2x), D (2x), B (fade out) | ||

There's the song. Now, let's analyze!

The shifts between C and D

Although the song spends time in (arguably) three different keys, C and D are featured most prominently. Each verse is in C, and each chorus begins in D. So let's start with the question: how does the song travel between C and D so smoothly?

What's similar. First, consider what's similar about the verse and chorus. Why do they sound like they're in the same song even though they're in different keys? Of course, each section contains the same chords, just transposed. More intriguingly, the sections share chords even in their transposed form. Compare the chords in C: (C Gm Dm Fm) with the chords in D: (D Am Em Gm). One chord is the same (Gm), and two (D and Dm) are highly similar.

The pitches in the verse and chorus tunes have much in common as well - the verse uses C, D, E, F, and G, while the chorus uses D, E, F#, and G. Notice also that the pitches of the chorus fit within the C-G range defined by the verse! In fact, the only the other key where this would be true would be C#, and a chorus in that key would have all new pitches. So, the shift to D keeps the melody in essentially the same place.

Furthermore, it can be shown via basic Schenkerian analysis (though not in this blog) that the dominant melodic pitch over the first two chords is G. After all, G is the goal of the first melody snippet, and unlike the other consonant melodic notes over the C chord - C and E - G is also consonant over the G minor chord. And it's pretty clear that the dominant pitch over the next two chords is F. By similar techniques, the chorus can be reduced to a move from F# down to D. Thus it is satisfying in a surprising way that the chorus fills in the gap in the verse we didn't know existed - the gap between G and F, which has one note, F#.

Okay, that was quite a mouthful, but I didn't have an easier way of stating it! But the basic idea is simple. Let me illustrate it by playing the dominant notes over each section, and you can hear the G, F, and F# in question:

| G | F | G | F | F# | |||||

| C | Gm | D | Fm | C | Gm | D | Fm | D | |

What's different. On the other hand, it's intriguing that some jarring differences between the verse and the chorus are left in place. The last chord of the verse (Fmi) and the first chord of the chorus (D) are quite remote, and there's no attempt to smooth out the shock with transitional material. It might help that the chord before that Fmi is a Dmi, though, as in, the last two chords of the verse plus the first chord of the chorus go Dmi-Fmi-D, so at least the D chord is familiar to our ear. But still, listen to how it sounds to jump from Fmi to D:

Nor is any effort made to create a smooth transition in the melody. The verse tune ends in C, and the chorus tune begins on F# - that's as remote as two pitches can be, a tritone. And yet, how would it sound if the song had a smoother transition?

The idea of adding material to make a smooth transition between the verse and chorus melodies simply doesn't fit in the style of the song. The verse and chorus have similarities, but the abruptness of the transition is left to hang there, and it's part of the charm. Nothing really smooths over the transition in the short term, but it makes sense in the long term, and the rhythm and energy of the song carry us through. We believe it in the short term because of the rhythm, and we believe it in the long term for the reasons given above - the surprise isn't really so surprising after all, but it's just catchy.

My old theory teacher, the great David Lewin, used to talk about "counterpoint by force of will" - if two unrelated melodies were played at the same time, but played really loud, the listener would have to believe they belonged together. Why else were they being played together so loudly? This is similar - modulation by force of will, and modulation between two sections which have enough similarities to make it work.

This contrasts to "Let's Hear it for the Boy", a song written by professional songwriters, where a pre-chorus gets us to the chorus in D, and a quick transition gets us back to the verse in C. It contrasts similarly to "Jump for My Love". It would make for an interesting blog post to compare these two approaches! Someday…

The return from the first chorus in D to the second verse in C is even more sudden, but that suddenness is used in the service of creating a smoother transition. The chorus cuts off suddenly before the last word, like this:

The full hook, "Our house in the middle of our street", ends on the notes F# ("our") and D ("street"). At the end of the first chorus, the hook is cut off after "our", so it ends on F#. The next melodic pitch we hear is D, the first pitch in the verse, and thus, we still hear F#-D, but F# is the last note of the chorus, and D is the first note of verse. By this clever trick, without any new transitional material, the melodic motion is preserved - how smooth!

Helping this out, the last chord of the chorus, Gmi, is followed by the C that begins the verse, which is almost a regular V-I progression. Should the chord have been changed to G to make a proper V-I progression (G-C)? It does sound nice that way, but for my money, the Gmi-C is more sublime and prettier. It partially implies a proper cadence on C, but it fits with the language of the song, and it complies with the rules the song has set down for us, including, this chord progression shall never change except to change keys.

The shift to B

If it's a surprise when the chorus enters in D, it's even more radical when, halfway through, the second chorus drops down to B. Which begs the question - why B? Unlike in D, the chords and melody pitches in B have little in common with those in C. On the other hand, this time the melody connects us to the new key. Listen to the second chorus until the key change:

| F# E | E F# G F# E F# | D F# E | E F# G F# E F# | D# D# C# |

| (key of D) | (key of B) | |||

As the key changes, the tune that normally goes (E F# G F# E F# | D) now goes (E F# G F# E F# | D#). Only the last note changes to get to the new key, and it changes only by a half-step, to D#. And the chorus in the new key happens to begin on that same note - D#! This is the classic way to make a smooth modulation to a foreign key - by keeping the melody absolutely predictable.

What's more, just like the F# that began the D chorus filled in a gap, so does D# in the B chorus. It's easy to show that the chorus in D prolongs the notes F#, E, and D. You can hear it:

So, through the key change, the large-scale motion in that chorus goes F# - E - D - D#. Yes, the D# fills the gap between D and E left by the first half of the chorus, just as that F# filled the gap between the F and G of the first verse. It's all about the half-steps. And, to my ear, half-step moves help define that magical sound of a smooth modulation.

But we're not done with that F# yet. Just as the main notes of the chorus in D are F#, E, and D, the main notes of the chorus in B are D#, C#, and B. Although we spend the longest on the C#, it's really just a passing tone between D# and B. So after we jump down from F# in the D chorus to D# in the B chorus, the ear still hears that F# hanging over the B chorus, pleasantly prolonged by the D# and B that come next, forming the complete B major triad. F# clearly plays a pivotal role in this song, as it defines the modulation to D and anchors the entire chorus in B. You can hear it:

And now I'll play the F# over a compressed version of that whole chorus:

If this idea seems far-fetched, it didn't to whoever arranged the song, who made the influence of F# over the B chorus explicit by having violins play quarter-note F#'s for the entire section. And by putting in a single, loud, low guitar F# on the downbeat.

Here's another interesting thing about the sudden jump to B. List out all the chords the song uses before that jump, then sort that list by pitch, and you get (C Dm D Em Fm Gm Am). So, before the jump to B, the song uses a chord built on every note in the C major scale except for B. Then the move to B fills that gap!

So we can find various reasons to explain why B is a especially satisfying destination. Also, of course, once the song has broken the ice and change keys from C to D, the dam has broken loose, and the second key change is far less surprising than the first one. And, when we return abruptly to C for the third verse, by now we just accept it as part of the journey, part of the language of the song. Our ear has been trained!

Topics for further research

This post is already quite long, so I'm going to stop there. I do wish I could write more, as the more I explored this remarkable song, the more questions I wanted to explore. For example:

- There's a really unusual short extra instrumental section in G before the instrumental solo in C. Is this there to re-establish C? For some sort of other balance? Why?

- How about the other little melodic nuggets played by various instruments throughout the song? What does it mean that the sax solo covers the notes of the C scale left not used by the verse melody? Is it interesting that the first guitar line is built from the same five notes as the verse melody - and that both these phrases are built on five-note scale segments, just like the verse melody? (Probably.)

- And, most importantly: the song's main chord progression has two unusual chords - in C, it's the Gmi and Fmi which come, not from C major, but from C minor. Do those chords help destabilize C major, thus preparing the ear for key changes? Is their move to the flat side balanced out by the move to the sharp side that occurs when we get to D? Or is it just that the minor chord means, for example, when we to D, we then have a chord (Ami) that's in the key of C instead of Amaj? Or do those minor keys simply lend the song its "nostalgic" sound to match the lyrics that recollect a childhood home?

- Is it significant that, at the end of the song, the chorus finally occurs in C, the key of the verse?

And, in conclusion

I don't think this song would have much appeal if it never left C. Then, like most songs on the charts these days, it would be based on a constant, never-changing chord progression, and, in my humble opinion, it would quickly wear out its welcome. I assumed that the band had written the song that way, and an ambitious producer had come along, spruced it up with an ecstatic riot of key changes, and generally just awesomely arranged the song within an inch of its life. However, a couple of questions to friends led me to another Madness hit, "House of Fun," which exhibits the same tricks - verse in one key, chorus in another, chorus that changes keys halfway through. The members of Madness must have realized early on in their careers that a solid rhythmic groove and catchy, confident tunes could carry a song, and key changes could provide unpredictability. And that's what this song really shows - you've got to balance predictability and the unexpected, and that's just what they've done.

The song also shows a way to create complexity without including "trained musician" elements like transitions and altering chord progressions, simply sticking to "rock-like" elements. By not bothering to include transitional material to justify the key changes, and keeping everything in standard 4-bar phrases, it's almost as if the song is saying, these key changes are normal! They don't require any special treatment, they just work!

How about other songs that jump up a step for the chorus? Is that a common pattern? How about songs that have an introduction in one key but are otherwise entirely in another, like Wouldn't It Be Nice? And how about other songs that change keys more than once? Good Vibrations, anyone?

Oh, and:

Wikipedia tells me that Ruth Pointer became a grandmother in 1984, at the peak of the Pointer Sisters' chart success. How many other grandmothers have had top 10 hits? And have anyone else ever conveyed such joy in their videos?